The title appropriately evokes a spectral quality; a combined impermanence and innocence, characteristic of a meandering phantom. At the same time, it denotes a first attempt, an inaugural act, a debut.

It’s a series of metamorphoses, not totally uncharacteristic of the coming-of-age genre, but with an eerie underbelly—teens becoming ghosts, ghosts becoming visible (to us and one another), a suburb becoming haunted, celluloid and all of its imperfections becoming digital. The familiar—for those of us who are indeed familiar with suburban Canada—turning strange, not only by tilting the genre sideways, but by situating its audience in a landscape that oscillates between being a site of stagnation and a site of transformation; of preservation and loss; a mirror of suburban adolescence through characters both stuck in and transcending time. In his debut, Graham Foy captures an experience entirely hauntological: a ghostly state of being, a lament for futures snuffed out in suburbia, and a meditation on the often uncanny nature of the coming of age.

Halfway through the film, we are introduced to Whitney through one of the traces she leaves behind: a missing poster with large pink block letters, she’s pictured against the forest which would eventually swallow her up. Subsequent shots of the other posters pasted around Calgary show this document of her last sighting decaying from the elements. How long she has been missing is unclear. I see you are not here.

Another artifact is retrieved from the ravine. At this point in the film, we follow Whitney more closely as her life before and during her disappearance become the main subject of our observation. Pulled out from the rocks underneath the bridge, the little black diary is constantly in Whitney’s grasp, except for when she is instead gripping the straps of her purple sequin backpack; a striking and sparkly indicator that Whitney doesn’t quite fit in, and doesn’t really want to. I hated the suburbs… at the top of one of the pages. I hadn’t slept for weeks. I hadn’t dreamt. What do trains dream?

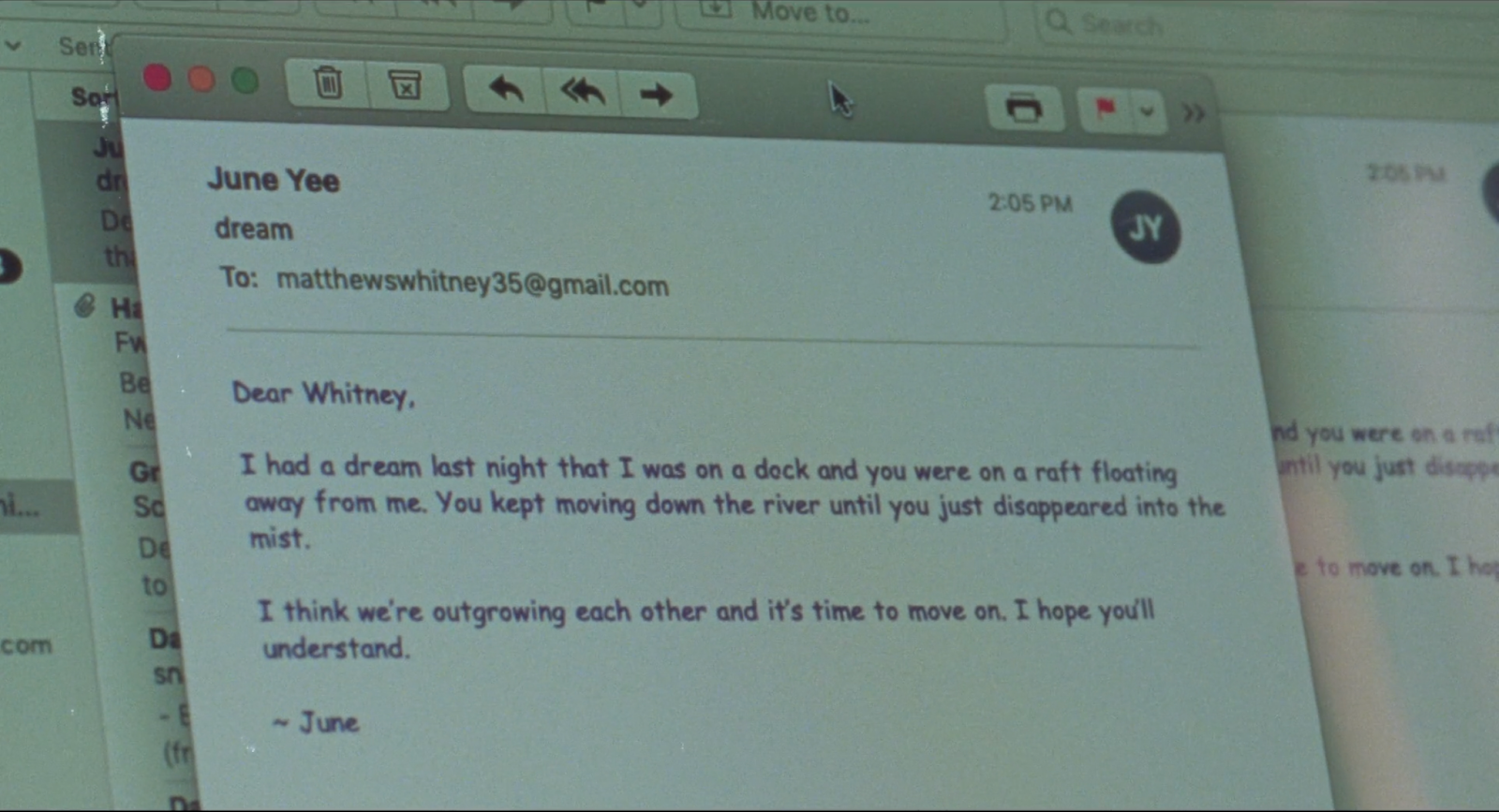

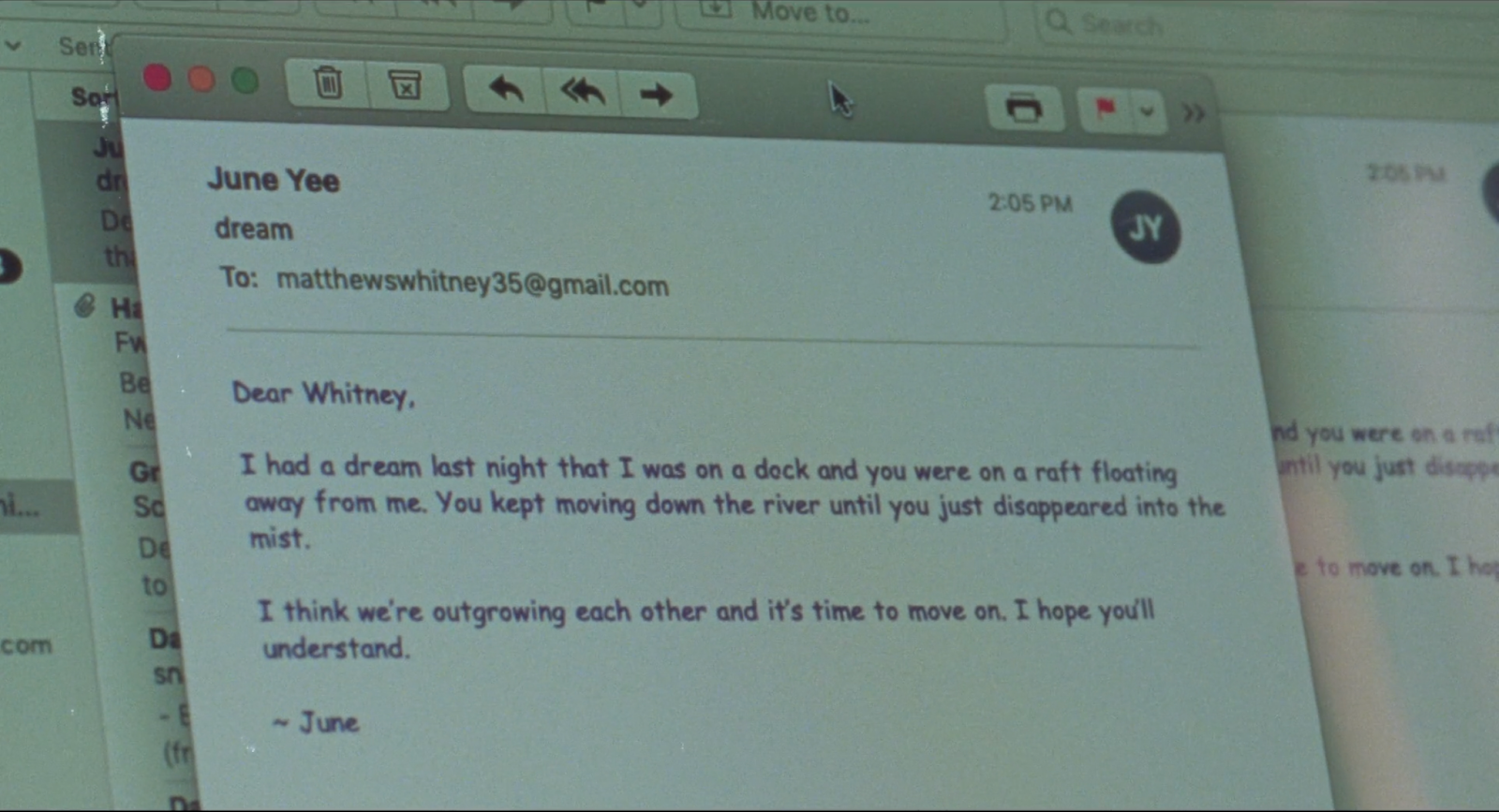

The train… fleeting, a barrelling force connecting present to past, a way out. You kept moving down the river until you just disappeared into the mist. There is a tradition in this film of sending things already dead down the river: a cat carcass discovered in an unfinished home’s basement, the shoe of a lost friend, and Whitney herself, disappearing and reappearing to us in past and present. Her ill-fated maiden voyage is swallowed by fog, her death sentence spelled out in purple Comic Sans. No longer a child but not yet adult, like the suburbs she is perpetually in construction. How can you be outgrowing me if I feel so stagnant?

The last sequence of the film returns us to a house in construction. A small tape deck seen near the beginning of the film, evidence of someone who once worked on the unfinished structure, sits waiting for Kyle—his own trace scattered around Calgary in the form of a graffiti tag which gives the film its name—and Whitney. She rewinds, then presses play; a return, a repeating, a doubling of sorts. The crackling voice of Roger Miller reflects across the sturdy bones of the unfinished structure, as two lonely ghosts lie upon each other. Whatever I leave behind will tell you what I am not.

My dear heart, seems like a year since you’ve been out of my sight/A single room, a table for one/It’s a lonesome town alright…

The film itself is a preservation of loss; the dust and scratches on screen, whether acquired in camera or during the scanning process necessary in converting 16mm to digital, become spectral themselves through their not-quite-tangible allure. “A love letter to Calgary,” according to lead actor Jackson Sluiter, written in graffiti across sites still in progress, and ravines which revive dead cats and lonely teenagers. A mounting collection of traces that create an archive across a suburban landscape, documenting the ghosts that once lived there, or perhaps still do.

***

Sometimes I go home to London; in my mind, a wasteland, a site teeming with old insecurity, my melancholic adolescence splayed out in front of me through antiquated shopping plazas, abandoned buildings, and stretches of barren construction sites leading into farmland. Like traversing backwards, time stagnating, though I know it’s gone forward because there are different shops at the mall, my nieces have grown to be more than half my size. The posters from my teenage bedroom, now occupied by my younger sister, stacked in a pile with my old sketchbooks, filled with practiced graffiti tags that i had only had the courage to do twice: once on the mailbox at the end of our street, now painted over, and once on the no littering sign in the nearby forest, immediately replaced by the city. I think she still lives there, a teenage phantom obsessed with her own permanence, with proving that she existed, and leaving a trace that lasted.

The title appropriately evokes a spectral quality; a combined impermanence and innocence, characteristic of a meandering phantom. At the same time, it denotes a first attempt, an inaugural act, a debut.

It’s a series of metamorphoses, not totally uncharacteristic of the coming-of-age genre, but with an eerie underbelly—teens becoming ghosts, ghosts becoming visible (to us and one another), a suburb becoming haunted, celluloid and all of its imperfections becoming digital. The familiar—for those of us who are indeed familiar with suburban Canada—turning strange, not only by tilting the genre sideways, but by situating its audience in a landscape that oscillates between being a site of stagnation and a site of transformation; of preservation and loss; a mirror of suburban adolescence through characters both stuck in and transcending time. In his debut, Graham Foy captures an experience entirely hauntological: a ghostly state of being, a lament for futures snuffed out in suburbia, and a meditation on the often uncanny nature of the coming of age.

Halfway through the film, we are introduced to Whitney through one of the traces she leaves behind: a missing poster with large pink block letters, she’s pictured against the forest which would eventually swallow her up. Subsequent shots of the other posters pasted around Calgary show this document of her last sighting decaying from the elements. How long she has been missing is unclear. I see you are not here.

Another artifact is retrieved from the ravine. At this point in the film, we follow Whitney more closely as her life before and during her disappearance become the main subject of our observation. Pulled out from the rocks underneath the bridge, the little black diary is constantly in Whitney’s grasp, except for when she is instead gripping the straps of her purple sequin backpack; a striking and sparkly indicator that Whitney doesn’t quite fit in, and doesn’t really want to. I hated the suburbs… at the top of one of the pages. I hadn’t slept for weeks. I hadn’t dreamt. What do trains dream?

The train… fleeting, a barrelling force connecting present to past, a way out. You kept moving down the river until you just disappeared into the mist. There is a tradition in this film of sending things already dead down the river: a cat carcass discovered in an unfinished home’s basement, the shoe of a lost friend, and Whitney herself, disappearing and reappearing to us in past and present. Her ill-fated maiden voyage is swallowed by fog, her death sentence spelled out in purple Comic Sans. No longer a child but not yet adult, like the suburbs she is perpetually in construction. How can you be outgrowing me if I feel so stagnant?

The last sequence of the film returns us to a house in construction. A small tape deck seen near the beginning of the film, evidence of someone who once worked on the unfinished structure, sits waiting for Kyle—his own trace scattered around Calgary in the form of a graffiti tag which gives the film its name—and Whitney. She rewinds, then presses play; a return, a repeating, a doubling of sorts. The crackling voice of Roger Miller reflects across the sturdy bones of the unfinished structure, as two lonely ghosts lie upon each other. Whatever I leave behind will tell you what I am not.

My dear heart, seems like a year since you’ve been out of my sight/A single room, a table for one/It’s a lonesome town alright…

The film itself is a preservation of loss; the dust and scratches on screen, whether acquired in camera or during the scanning process necessary in converting 16mm to digital, become spectral themselves through their not-quite-tangible allure. “A love letter to Calgary,” according to lead actor Jackson Sluiter, written in graffiti across sites still in progress, and ravines which revive dead cats and lonely teenagers. A mounting collection of traces that create an archive across a suburban landscape, documenting the ghosts that once lived there, or perhaps still do.

***

Sometimes I go home to London; in my mind, a wasteland, a site teeming with old insecurity, my melancholic adolescence splayed out in front of me through antiquated shopping plazas, abandoned buildings, and stretches of barren construction sites leading into farmland. Like traversing backwards, time stagnating, though I know it’s gone forward because there are different shops at the mall, my nieces have grown to be more than half my size. The posters from my teenage bedroom, now occupied by my younger sister, stacked in a pile with my old sketchbooks, filled with practiced graffiti tags that i had only had the courage to do twice: once on the mailbox at the end of our street, now painted over, and once on the no littering sign in the nearby forest, immediately replaced by the city. I think she still lives there, a teenage phantom obsessed with her own permanence, with proving that she existed, and leaving a trace that lasted.