My Problematic Fave: A juicy question with many answers: Catherine Breillat. Dollarama. Nina Simone's version of "I Loves You, Porgy" (it's not on Simone, she saves it from Gershwin, it's just the one I love). I would say Woody Allen's Husbands and Wives or Deconstructing Harry, but I think it's okay to enjoy those (so bleak and revealing, they are basically a confession), it's more problematic that I love Manhattan.

First Movie I went on a Date for: Sweet Home Alabama, a double date with my neighbourhood friend and two guys from another school we met hanging out (as teens do) after school hours at the playground. He thought I was crying during an emotional scene where Reese Witherspoon visits a grave in her hometown (A grandparent? Childhood dog?), but I was a cynical 14-year-old, and not then or now a Rom Com girl, and was trying to muffle my laughter.

My Movie/TV Character Style Icon: Julia Stiles in Hamlet, Kiera Knightley in Love, Actually, Satine in Moulin Rouge, Maggie Cheung and Nathalie Richard in Irma Vep.

The First Sex Scene I Ever Saw: I can't remember for sure, but probably Titanic.

… and it made me feel: Confused: it gave me absolutely no information on what sex actually is, only that there were certain signals I would one day understand (like the men who laugh knowingly when they see the fogged up windows). Also afraid: it seemed sex would always leave some trace, and you could not hide it from anyone. Also romantic: sex was fun and actually fine, no one was hurt by it or punished for it (although it did happen right before they hit the iceberg, but this was not a coincidence that my young mind internalized.)

Best Needle Drop: Most of the songs in Rushmore (but maybe "Oo La La" by The Faces the most). I didn't even know what those songs were when I watched it at 15, but I knew that they were perfect.

I Wish this Fictional Meal Existed IRL: This meal does exist, but I have never seen the timpano from Big Night out in the wild, and although it seems like something that is better in theory than in execution, I'm not sure I'll feel fully satisfied if I never try one.

Untouchable Classic that I hate: How do I even pick! Citizen Kane does very little for me (except Welles, who I find quite hot), 2001: A Space Odyssey is glacial and so British (I do think the scene approaching the monolith on the moon is fab), Bresson leaves me dry (a symptom, perhaps, of him casting actors because they're hot), I find Parasite shallow, I only like the scenes in Stalker before and after they go to the Zone, and I can't get past Jeanne Dielman's melodramatic ending (which became an irritating staple of art house film).

Celebrity I had on my wall as a teen

Frank Black Francis and Karen O.

My film/TV OTP is: I can't think of a time when I felt the ending of a film or show should have been different, I like when characters come together, I like when they fall apart.

The Reality TV Show I Would Win: I think it's obvious that my true place is not as a competitor, but as a judge.

“Even the most gracious of young girls is a terrible devourer, not because of her soul but because of her dreams. Beware of the Other’s dream”, says the static clip of Gilles Deleuze in the video letter Bertrand Bonello writes to his daughter. In Coma (2022), Bonello ponders aloud: Where does my daughter disappear when she goes into her bedroom? What are her hopes and dreams? Is this an escape or a retreat?

When my parents finally decided that I was too old to share a bedroom with my brother, I would stay up late fantasizing about what this spectacular homecoming would look like. I began to dream in moodboards, meticulously picking out each object, dressing my bookshelf like it was a set piece: A print of Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital, a defunct red typewriter, a secular saint candle of Freud (never lit). These objects were conscious externalizations of who I wanted to be now that I had the space to become it.

"When I finally had the chance to paint the walls of my room, I painted them in shades of me."

My friend covered his room, wall to ceiling, with movie posters, cataloguing his consumption through low-res stock images printed at the library. Another, disillusioned with paper, took black Sharpie straight to the wall for her wallowing poetry. The heightened emotionality of adolescence turns every available surface into a diary page—every feeling must be expressed, every thought must be documented, and every corner must be collaged.

When I finally had the chance to paint the walls of my room, I painted them in shades of me.

In Gregg Araki’s Nowhere (1997), this literalization of the psyche is splayed out in technicolour. A mural of the loverboy Dark (played by the luscious James Duval) blowing his brains out stretches across his otherwise sparse bedroom, a vivid and inescapable expression of his suffering that begs to be acknowledged. Araki’s filmography celebrates the hyper-individualist escapism of teenagehood, where the nascent possibility of rejecting the world that has rejected us first presents itself. When a dreamy Dark grows deaf to his mother banging on his bedroom door, his insolence is also an assertion; his bedroom is his first attempt to carve out a space of his own.

"...his bedroom is his first attempt to carve out a space of his own."

While traditional coming-of-age narratives attribute the adolescent’s maturation to contact with the real world, I think that the mythology of ourselves is constructed late at night, under the covers, in the womb of our bedrooms. “Teenager's rooms have always existed as a parallel universe to the domestic family home—the only place you have complete control, and a kind of purgatory where you exist until you escape,” says Luke Goodsell, who runs a Tumblr dedicated to Teenage Bedrooms on Screen. “As essential hideaways and shrines to ego, they're pretty much fundamentally the same from the ‘50s till now,” he elaborates. If the bedroom is a facade, then there has never been a truer one.

In this regard, interior design is not unlike fashion.The looks in Araki's Teenage Apocalypse trilogy are highly stylized and overcurated in the predictable way you’d expect an 18-year-old kid from LA to be, an idiosyncratic maximalism that has found its descendant in the ultra-hip Heaven by Marc Jacobs. But while fashion is an outward bid for recognition, the bedroom is not only a bid to be seen, but a bid to become. At various points in Nowhere, this threshold is transgressed, and the two blend into one another, co-conspiring to imbue the teens’ self-spiralling narratives with significance. A single brushstroke coats Mel (the coquettish Rachel True) and her bedroom, a Twister-map-terrority that invites playful complications from her various paramours.

According to Julia Kristeva, this transfusion lends itself to the abject, a state where “a threatened breakdown in meaning is caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object or between self and other.” This in-betweenness allows us to access something that is first concealed, and then lost to the moral dictates, perfunctory routines and contracted relationships of the adult world. Araki, too, honours the in-betweenness of adolescence, assigning his characters an agency that’s fallible. In the neon wasteland of his California, innocence is continually lost and regained, shaky and unstable like the video captured on Dark’s camcorder. It is profound “to first imagine this in-between space, this topos of incompleteness that is also that of all possibilities, of the everything is possible,”says Kristeva. Adolescence is a blank wall we are waiting to fill.

"Adolescence is a blank wall we are waiting to fill."

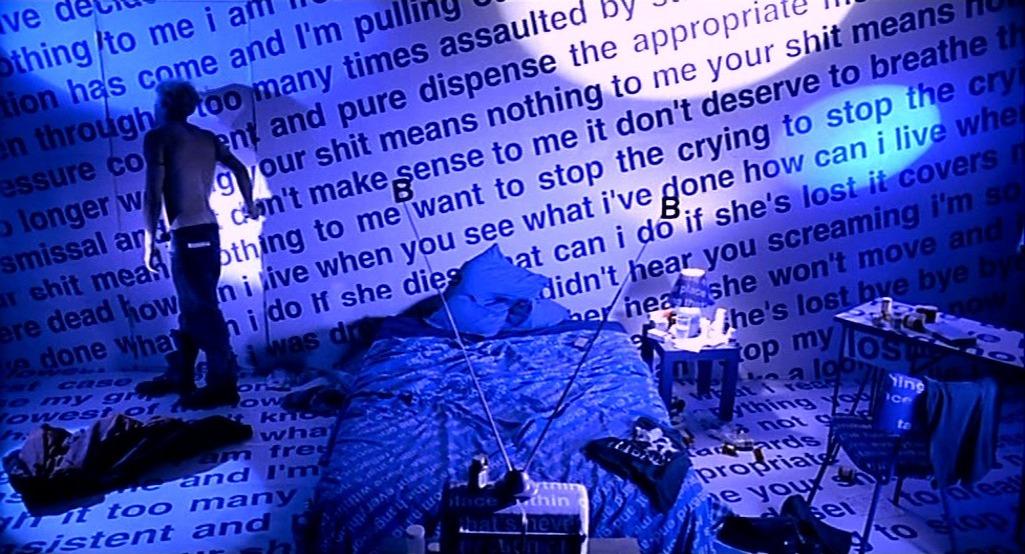

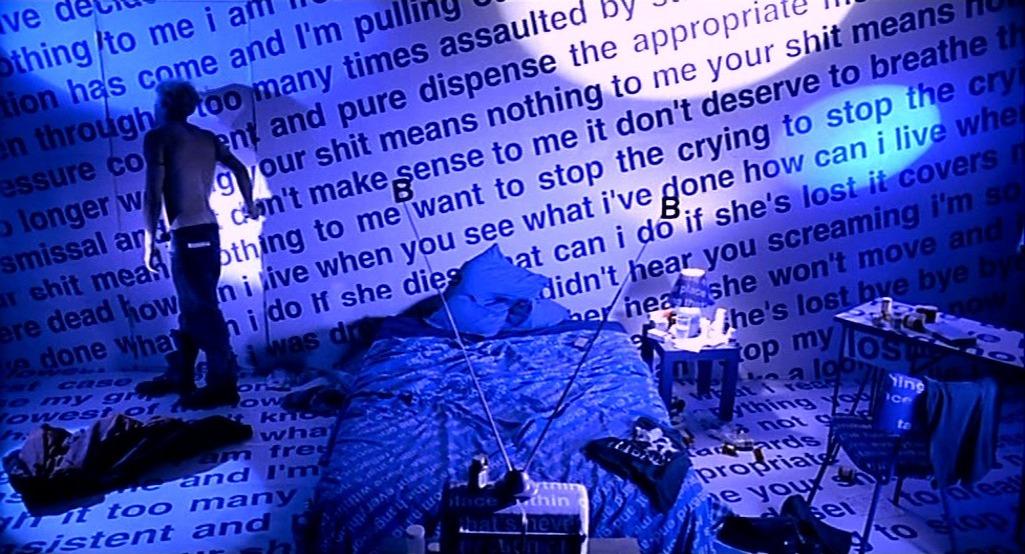

Kristeva believes that the novelistic genre (one that puts the self at the centre of everything) itself belongs to the adolescent economy, an “immature state, as depressive as it is jubilatory, to which we owe, perhaps, some part of the pleasure called ‘aesthetic’”(from The Adolescent Novel). Language fails Bart (played glassily by Jeremy Jordan) in the throes of his heroin addiction. His inner turmoil is misunderstood by his lover, whose ultimatums render him mute. This mutual unintelligibility extends to his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Sighvatsson, Icelandic caricatures who chastise him in strange and sharp tongues (despite the fact that Nowhere is a film with actual aliens, it is often those closest to the teens who are cast as the most distant and foreign). Bart’s room, in contrast, is a novelistic cocoon, walls sprawled full of all the words he can’t quite bring himself to say. When we are ill-equipped to make our interiority legible to those around us, it finds a way to leak out anyways.

The most intimate relationship a girl will ever have does not take place in her bedroom; rather, it is the one she shares with it. In bloom and delicate like a flower, Egg (played by a wide-eyed Sarah Lassez) is lavishly courted and then mercilessly brutalized by a Baywatch starlet (Jaason Simmons, who is cast literally as The Teen Idol ). She is swept up in the fantasy transmitted on her bedroom TV, and to her bedroom TV she returns when it shatters—a sanctuary for her to languish in her pain, shame and horror. Against Egg’s bleeding body, her perfect pastel bedroom takes on an ironic, almost cruel shape. The same flowerbeds that spring out of the garden are the ones that litter the grave.

Like an incantation, the ephemera of my bedroom was meant to summon the woman I hoped to become, a space free from leering eyes where my existence preceded my essence. “I understand by the term 'adolescent' less an age category and more an open psychic structure…thanks to a tremendous loosening of the superego," says Kristeva. The teenage girl is tragic and amorphous like a lump, like a broken egg, like an undetermined growth that may metastasize. Yet she dresses her tragedy up in tinsel, squeezes herself into a shape, attempting to articulate something she is yet to understand. Bonello is attempting to understand it too. In Coma, he dissects his daughter’s bedroom through various mediums, enshrining it in a mythic intrigue. He imagines it as not only a physical space—the bookshelf, the messy desk, the postcards tacked onto the wall—but a mystical realm where her dreams and fantasies run without restraint. In the confines of L'adolescente’s (played by a baby-faced Louise Labéque) bedroom, reality is abandoned: the dolls of her diorama come alive, acting and reenacting taboo desires that she never would, the frame mutates into bright and crude animations, the bedroom becomes artificial—like the dolls, into something our protagonist can control and manipulate.

What she cannot control, though, asserts itself continuously. Over FaceTime, we peer into the bedrooms of other teenage girls, each at the helm of their own little kingdoms from which she has been exiled. As the adolescent switches between multiple tabs, we see her drawn into the perverse worlds of serial killers, wellness bloggers, and predatory algorithms—a digital stream of consciousness that spirals headlessly out of her fingertips. She devours her cyberspace in the same way she consumes the image outside her bedroom window—at a distance, and with longing.

The protagonists’ laptop is not unlike a diary, which is not unlike a bedroom: serving both as a portal into other realities and into the deep and dark recesses of her own mind. As the world (whether through disease or policy or simple loneliness) is plunged further into isolation, we retreat into our shadowy bedrooms more and more; the cushiony seclusion it once offered us in our youth has proved to be too suffocating. The anarchic freedom of adolescence was always meant to be transient—a necessary layover in a greater, grander, vaster journey that extends beyond the self.

But some of us emerged from our bedrooms to find nothing awaiting us, and so we turned right back around. “You can see it in our eyes. It's in mine, look. I'm doomed. I'm only 18 years old and I'm totally doomed,” Dark pontificates in his diary, lying petrified in his room, as we lie petrified in ours. When we finally leave our bedrooms, what creature will emerge?

“Even the most gracious of young girls is a terrible devourer, not because of her soul but because of her dreams. Beware of the Other’s dream”, says the static clip of Gilles Deleuze in the video letter Bertrand Bonello writes to his daughter. In Coma (2022), Bonello ponders aloud: Where does my daughter disappear when she goes into her bedroom? What are her hopes and dreams? Is this an escape or a retreat?

When my parents finally decided that I was too old to share a bedroom with my brother, I would stay up late fantasizing about what this spectacular homecoming would look like. I began to dream in moodboards, meticulously picking out each object, dressing my bookshelf like it was a set piece: A print of Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital, a defunct red typewriter, a secular saint candle of Freud (never lit). These objects were conscious externalizations of who I wanted to be now that I had the space to become it.

"When I finally had the chance to paint the walls of my room, I painted them in shades of me."

My friend covered his room, wall to ceiling, with movie posters, cataloguing his consumption through low-res stock images printed at the library. Another, disillusioned with paper, took black Sharpie straight to the wall for her wallowing poetry. The heightened emotionality of adolescence turns every available surface into a diary page—every feeling must be expressed, every thought must be documented, and every corner must be collaged.

When I finally had the chance to paint the walls of my room, I painted them in shades of me.

In Gregg Araki’s Nowhere (1997), this literalization of the psyche is splayed out in technicolour. A mural of the loverboy Dark (played by the luscious James Duval) blowing his brains out stretches across his otherwise sparse bedroom, a vivid and inescapable expression of his suffering that begs to be acknowledged. Araki’s filmography celebrates the hyper-individualist escapism of teenagehood, where the nascent possibility of rejecting the world that has rejected us first presents itself. When a dreamy Dark grows deaf to his mother banging on his bedroom door, his insolence is also an assertion; his bedroom is his first attempt to carve out a space of his own.

"...his bedroom is his first attempt to carve out a space of his own."

While traditional coming-of-age narratives attribute the adolescent’s maturation to contact with the real world, I think that the mythology of ourselves is constructed late at night, under the covers, in the womb of our bedrooms. “Teenager's rooms have always existed as a parallel universe to the domestic family home—the only place you have complete control, and a kind of purgatory where you exist until you escape,” says Luke Goodsell, who runs a Tumblr dedicated to Teenage Bedrooms on Screen. “As essential hideaways and shrines to ego, they're pretty much fundamentally the same from the ‘50s till now,” he elaborates. If the bedroom is a facade, then there has never been a truer one.

In this regard, interior design is not unlike fashion.The looks in Araki's Teenage Apocalypse trilogy are highly stylized and overcurated in the predictable way you’d expect an 18-year-old kid from LA to be, an idiosyncratic maximalism that has found its descendant in the ultra-hip Heaven by Marc Jacobs. But while fashion is an outward bid for recognition, the bedroom is not only a bid to be seen, but a bid to become. At various points in Nowhere, this threshold is transgressed, and the two blend into one another, co-conspiring to imbue the teens’ self-spiralling narratives with significance. A single brushstroke coats Mel (the coquettish Rachel True) and her bedroom, a Twister-map-terrority that invites playful complications from her various paramours.

According to Julia Kristeva, this transfusion lends itself to the abject, a state where “a threatened breakdown in meaning is caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object or between self and other.” This in-betweenness allows us to access something that is first concealed, and then lost to the moral dictates, perfunctory routines and contracted relationships of the adult world. Araki, too, honours the in-betweenness of adolescence, assigning his characters an agency that’s fallible. In the neon wasteland of his California, innocence is continually lost and regained, shaky and unstable like the video captured on Dark’s camcorder. It is profound “to first imagine this in-between space, this topos of incompleteness that is also that of all possibilities, of the everything is possible,”says Kristeva. Adolescence is a blank wall we are waiting to fill.

"Adolescence is a blank wall we are waiting to fill."

Kristeva believes that the novelistic genre (one that puts the self at the centre of everything) itself belongs to the adolescent economy, an “immature state, as depressive as it is jubilatory, to which we owe, perhaps, some part of the pleasure called ‘aesthetic’”(from The Adolescent Novel). Language fails Bart (played glassily by Jeremy Jordan) in the throes of his heroin addiction. His inner turmoil is misunderstood by his lover, whose ultimatums render him mute. This mutual unintelligibility extends to his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Sighvatsson, Icelandic caricatures who chastise him in strange and sharp tongues (despite the fact that Nowhere is a film with actual aliens, it is often those closest to the teens who are cast as the most distant and foreign). Bart’s room, in contrast, is a novelistic cocoon, walls sprawled full of all the words he can’t quite bring himself to say. When we are ill-equipped to make our interiority legible to those around us, it finds a way to leak out anyways.

The most intimate relationship a girl will ever have does not take place in her bedroom; rather, it is the one she shares with it. In bloom and delicate like a flower, Egg (played by a wide-eyed Sarah Lassez) is lavishly courted and then mercilessly brutalized by a Baywatch starlet (Jaason Simmons, who is cast literally as The Teen Idol ). She is swept up in the fantasy transmitted on her bedroom TV, and to her bedroom TV she returns when it shatters—a sanctuary for her to languish in her pain, shame and horror. Against Egg’s bleeding body, her perfect pastel bedroom takes on an ironic, almost cruel shape. The same flowerbeds that spring out of the garden are the ones that litter the grave.

Like an incantation, the ephemera of my bedroom was meant to summon the woman I hoped to become, a space free from leering eyes where my existence preceded my essence. “I understand by the term 'adolescent' less an age category and more an open psychic structure…thanks to a tremendous loosening of the superego," says Kristeva. The teenage girl is tragic and amorphous like a lump, like a broken egg, like an undetermined growth that may metastasize. Yet she dresses her tragedy up in tinsel, squeezes herself into a shape, attempting to articulate something she is yet to understand. Bonello is attempting to understand it too. In Coma, he dissects his daughter’s bedroom through various mediums, enshrining it in a mythic intrigue. He imagines it as not only a physical space—the bookshelf, the messy desk, the postcards tacked onto the wall—but a mystical realm where her dreams and fantasies run without restraint. In the confines of L'adolescente’s (played by a baby-faced Louise Labéque) bedroom, reality is abandoned: the dolls of her diorama come alive, acting and reenacting taboo desires that she never would, the frame mutates into bright and crude animations, the bedroom becomes artificial—like the dolls, into something our protagonist can control and manipulate.

What she cannot control, though, asserts itself continuously. Over FaceTime, we peer into the bedrooms of other teenage girls, each at the helm of their own little kingdoms from which she has been exiled. As the adolescent switches between multiple tabs, we see her drawn into the perverse worlds of serial killers, wellness bloggers, and predatory algorithms—a digital stream of consciousness that spirals headlessly out of her fingertips. She devours her cyberspace in the same way she consumes the image outside her bedroom window—at a distance, and with longing.

The protagonists’ laptop is not unlike a diary, which is not unlike a bedroom: serving both as a portal into other realities and into the deep and dark recesses of her own mind. As the world (whether through disease or policy or simple loneliness) is plunged further into isolation, we retreat into our shadowy bedrooms more and more; the cushiony seclusion it once offered us in our youth has proved to be too suffocating. The anarchic freedom of adolescence was always meant to be transient—a necessary layover in a greater, grander, vaster journey that extends beyond the self.

But some of us emerged from our bedrooms to find nothing awaiting us, and so we turned right back around. “You can see it in our eyes. It's in mine, look. I'm doomed. I'm only 18 years old and I'm totally doomed,” Dark pontificates in his diary, lying petrified in his room, as we lie petrified in ours. When we finally leave our bedrooms, what creature will emerge?