My Problematic Fave: A juicy question with many answers: Catherine Breillat. Dollarama. Nina Simone's version of "I Loves You, Porgy" (it's not on Simone, she saves it from Gershwin, it's just the one I love). I would say Woody Allen's Husbands and Wives or Deconstructing Harry, but I think it's okay to enjoy those (so bleak and revealing, they are basically a confession), it's more problematic that I love Manhattan.

First Movie I went on a Date for: Sweet Home Alabama, a double date with my neighbourhood friend and two guys from another school we met hanging out (as teens do) after school hours at the playground. He thought I was crying during an emotional scene where Reese Witherspoon visits a grave in her hometown (A grandparent? Childhood dog?), but I was a cynical 14-year-old, and not then or now a Rom Com girl, and was trying to muffle my laughter.

My Movie/TV Character Style Icon: Julia Stiles in Hamlet, Kiera Knightley in Love, Actually, Satine in Moulin Rouge, Maggie Cheung and Nathalie Richard in Irma Vep.

The First Sex Scene I Ever Saw: I can't remember for sure, but probably Titanic.

… and it made me feel: Confused: it gave me absolutely no information on what sex actually is, only that there were certain signals I would one day understand (like the men who laugh knowingly when they see the fogged up windows). Also afraid: it seemed sex would always leave some trace, and you could not hide it from anyone. Also romantic: sex was fun and actually fine, no one was hurt by it or punished for it (although it did happen right before they hit the iceberg, but this was not a coincidence that my young mind internalized.)

Best Needle Drop: Most of the songs in Rushmore (but maybe "Oo La La" by The Faces the most). I didn't even know what those songs were when I watched it at 15, but I knew that they were perfect.

I Wish this Fictional Meal Existed IRL: This meal does exist, but I have never seen the timpano from Big Night out in the wild, and although it seems like something that is better in theory than in execution, I'm not sure I'll feel fully satisfied if I never try one.

Untouchable Classic that I hate: How do I even pick! Citizen Kane does very little for me (except Welles, who I find quite hot), 2001: A Space Odyssey is glacial and so British (I do think the scene approaching the monolith on the moon is fab), Bresson leaves me dry (a symptom, perhaps, of him casting actors because they're hot), I find Parasite shallow, I only like the scenes in Stalker before and after they go to the Zone, and I can't get past Jeanne Dielman's melodramatic ending (which became an irritating staple of art house film).

Celebrity I had on my wall as a teen

Frank Black Francis and Karen O.

My film/TV OTP is: I can't think of a time when I felt the ending of a film or show should have been different, I like when characters come together, I like when they fall apart.

The Reality TV Show I Would Win: I think it's obvious that my true place is not as a competitor, but as a judge.

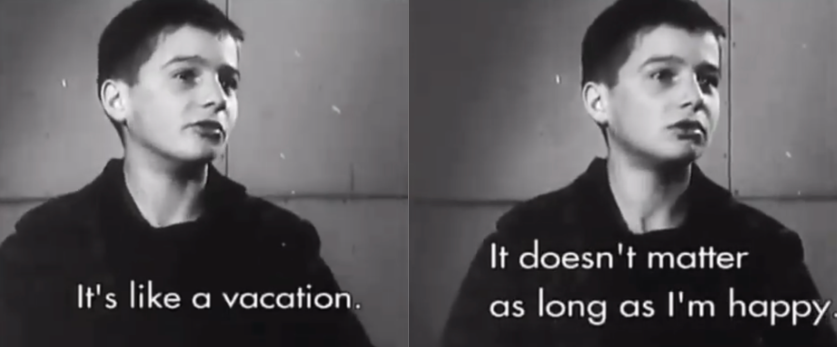

The video clip that will become the subject of this postcard was shot on 16mm film and is one minute thirty seconds long. It’s the audition interview that took place in 1958 between a 26-year-old François Truffaut, who was casting his first feature film, The 400 Blows (1959), and Jean-Pierre Léaud, 14, who was skipping school. The latter took a train spécialement to come to Paris for his audition for the lead role of Antoine Doinel: “It’s like a vacation for me.” That’s one of the twenty sentences Léaud speaks to Truffaut over the course of the interview, or miracle, that was made possible by luck and a letter, as well as a pair of industry parents, but I won’t linger on that last part, it sullies my note with nepotism—boring!—and ultimately isn’t that important since Truffaut is the one who created Léaud. Or: Léaud is the one who created Truffaut. Alternate translation: Truffaut was made by Léaud was made by Truffaut was made by Antoine Doinel was made by Truffaut was made by Léaud was made by Antoine Doinel Antoine Doinel Antoine Doinel on t’aime Doinel I love you Léaud. I hope you can read my handwriting. I’m rushing. I feel an outsized pressure to say everything on an undersized rectangle, so I have to scrunch my words. I started this postcard on the train to Marseille from Paris, which is why the return address is 16 rue Lacépède, 75005. Now I’m just a visitor and don’t have an address in Paris—cue the violins, by which I mean the slurred melody of "Thème de Camille" composed by Georges Delerue for Contempt (1963)—but that’s where I used to live. It was a time when I was learning French and didn’t think much about movies but had already come to understand that one answer to the task of living is walking in Paris. Sorry, adoring Paris is also boring, but sometimes it must be done. After all, I’m on vacation and this is a postcard: give me a break, or at least that sentence. Anyway, after I stopped living there—which is to say after I learned French, started watching Léaud in movies, after he became my subject—I was told that Léaud lived on that same street, and still does. I gaped like a goon but then the story turned sad. An image of him shuffling towards the Jardin des Plantes; another image of him slouching outside the corner boulangerie with a care worker; the fact that in 2023—the same year that Jean Eustache’s 1973 epic The Mother and the Whore was making its way through cinemas worldwide in a newly restored 4K version, and Léaud, the silk-scarved sunglassed black-booted dandy at its heart, was being discovered by a new generation—it was made known to film critic and Truffaut biographer Serge Toubiana that Léaud and his wife, Brigitte Duvivier, a retired literature professor, were in a “state of precarity at once material, mental, and physical.” Toubiana to Télérama (in my English): “There is a massive discrepancy between Léaud’s notoriety and his difficult living conditions.” A crowdfund was mobilized — first discreetly, among film workers, and then made public after Toubiana alerted the organization Amis de François Truffaut so that Léaud’s fans, friends, and admirers would be made aware and have the opportunity to contribute. The fund was called “Support and recognition for Jean-Pierre Léaud” and in a few days’ time it raised more than 20,000 euros from 456 people. I want to tell you that Léaud holds copyright for the Antoine Doinel films—Truffaut made sure of this right before he died. It was a final act of generosity to Léaud, who began for Truffaut as a loopy signature and became a 25-years-long answer. But first there were questions. And even though I only have two inches left on this postcard, I’m going to quote part of their first exchange in full. Léaud is the only person we see in the video, by the way; Truffaut is present as a voice behind the camera. Truffaut says: “They [your schoolteachers] won’t be happy, you missing school like this.” Léaud shoots back: “That doesn’t matter as long as I’m happy.” And then one last question before Truffaut shouts coupé, is: “In life, are you happy or sad?” And to this Léaud responds even faster: “Oh, I’m happy, not sad!” At 29, doing post-Cannes promotion for The Mother and the Whore (1973) and Truffaut’s Day for Night (1973)—both of which had just premiered and astonished—Léaud said about this interview that “[t]here was this little 13-year-old child. […] And when I saw those screen tests again […] I could see that that child was already aware that it was one of the most important moments in his life, that he had to get that part in that movie. I saw an impressive amount of willpower in those screen tests. […] The rest of the film was a kind of dream. Whenever I work with François, it’s like a vacation, or a dream, or a state of grace.” OK, last inch. I suggest you pause here to find a magnifying glass. Truffaut died at almost the same age as Balzac when Léaud was 40; as of this year, Léaud has lived 41 years in his wake. C’était pour Balzac, papa is what Doinel says to his father in The 400 Blows after his shrine catches fire, and I can imagine Léaud saying now, to a god or to the sea, looking at his entire life, C’était pour Truffaut. Ack, I did it again. I keep writing Truffaut with an X, like, True-Faux, True-False, Truffaut the true-false father in whose premature death contained a fraction of Léaud’s. The trust and play already activated in this video—this shrugged, stuttered clip that contains, as I've been trying to tell you, everything: the teenager, the glimmering beginning and also the end, always already the end because Léaud begins and ends with Truffaut. "A perpetual immaturity," ascribed the 2024 Cyril Leuthy documentary about Léaud to Léaud, which is to say a perpetual attachment to the teenager and also to grief, to the death of the faux father, and an attachment to the grieving of the child who survived childhood against all odds, against embarrassment, and against the melancholy that was of course always behind Léaud’s forcefully proclaimed teenaged happiness. I’m in Marseille now. I got here a few days ago and have been so consumed writing this postcard inside an apartment that I haven’t seen the water yet, a fact I know would make you writhe with frustration—you’re on vacation! But it matters that I’m writing on this huge, green Formica desk—itself a vacation, dream, or state of grace—and I’ve been told that it was once used in a movie set. Like Léaud, I am most at ease at Place Monge in Paris, wearing a jacket in mild weather, holding a book that is dry, eyes protected from the sun. The final scene of this postcard will, however, take place at the water, in a final bow to The 400 Blows. Rimbaud died here in Marseille, did you know that? I’ll say more about him in my next note—his relation to Truffaut and Léaud—this rhyming triplet of their sensibilities!—translation and acting, the words “clownish” and “blank” next to the words “comic” and “wild.” OK, I’m off. I’m going to the sea with a plan to throw this postcard into it and hope that it finds you soon.

The video clip that will become the subject of this postcard was shot on 16mm film and is one minute thirty seconds long. It’s the audition interview that took place in 1958 between a 26-year-old François Truffaut, who was casting his first feature film, The 400 Blows (1959), and Jean-Pierre Léaud, 14, who was skipping school. The latter took a train spécialement to come to Paris for his audition for the lead role of Antoine Doinel: “It’s like a vacation for me.” That’s one of the twenty sentences Léaud speaks to Truffaut over the course of the interview, or miracle, that was made possible by luck and a letter, as well as a pair of industry parents, but I won’t linger on that last part, it sullies my note with nepotism—boring!—and ultimately isn’t that important since Truffaut is the one who created Léaud. Or: Léaud is the one who created Truffaut. Alternate translation: Truffaut was made by Léaud was made by Truffaut was made by Antoine Doinel was made by Truffaut was made by Léaud was made by Antoine Doinel Antoine Doinel Antoine Doinel on t’aime Doinel I love you Léaud. I hope you can read my handwriting. I’m rushing. I feel an outsized pressure to say everything on an undersized rectangle, so I have to scrunch my words. I started this postcard on the train to Marseille from Paris, which is why the return address is 16 rue Lacépède, 75005. Now I’m just a visitor and don’t have an address in Paris—cue the violins, by which I mean the slurred melody of "Thème de Camille" composed by Georges Delerue for Contempt (1963)—but that’s where I used to live. It was a time when I was learning French and didn’t think much about movies but had already come to understand that one answer to the task of living is walking in Paris. Sorry, adoring Paris is also boring, but sometimes it must be done. After all, I’m on vacation and this is a postcard: give me a break, or at least that sentence. Anyway, after I stopped living there—which is to say after I learned French, started watching Léaud in movies, after he became my subject—I was told that Léaud lived on that same street, and still does. I gaped like a goon but then the story turned sad. An image of him shuffling towards the Jardin des Plantes; another image of him slouching outside the corner boulangerie with a care worker; the fact that in 2023—the same year that Jean Eustache’s 1973 epic The Mother and the Whore was making its way through cinemas worldwide in a newly restored 4K version, and Léaud, the silk-scarved sunglassed black-booted dandy at its heart, was being discovered by a new generation—it was made known to film critic and Truffaut biographer Serge Toubiana that Léaud and his wife, Brigitte Duvivier, a retired literature professor, were in a “state of precarity at once material, mental, and physical.” Toubiana to Télérama (in my English): “There is a massive discrepancy between Léaud’s notoriety and his difficult living conditions.” A crowdfund was mobilized — first discreetly, among film workers, and then made public after Toubiana alerted the organization Amis de François Truffaut so that Léaud’s fans, friends, and admirers would be made aware and have the opportunity to contribute. The fund was called “Support and recognition for Jean-Pierre Léaud” and in a few days’ time it raised more than 20,000 euros from 456 people. I want to tell you that Léaud holds copyright for the Antoine Doinel films—Truffaut made sure of this right before he died. It was a final act of generosity to Léaud, who began for Truffaut as a loopy signature and became a 25-years-long answer. But first there were questions. And even though I only have two inches left on this postcard, I’m going to quote part of their first exchange in full. Léaud is the only person we see in the video, by the way; Truffaut is present as a voice behind the camera. Truffaut says: “They [your schoolteachers] won’t be happy, you missing school like this.” Léaud shoots back: “That doesn’t matter as long as I’m happy.” And then one last question before Truffaut shouts coupé, is: “In life, are you happy or sad?” And to this Léaud responds even faster: “Oh, I’m happy, not sad!” At 29, doing post-Cannes promotion for The Mother and the Whore (1973) and Truffaut’s Day for Night (1973)—both of which had just premiered and astonished—Léaud said about this interview that “[t]here was this little 13-year-old child. […] And when I saw those screen tests again […] I could see that that child was already aware that it was one of the most important moments in his life, that he had to get that part in that movie. I saw an impressive amount of willpower in those screen tests. […] The rest of the film was a kind of dream. Whenever I work with François, it’s like a vacation, or a dream, or a state of grace.” OK, last inch. I suggest you pause here to find a magnifying glass. Truffaut died at almost the same age as Balzac when Léaud was 40; as of this year, Léaud has lived 41 years in his wake. C’était pour Balzac, papa is what Doinel says to his father in The 400 Blows after his shrine catches fire, and I can imagine Léaud saying now, to a god or to the sea, looking at his entire life, C’était pour Truffaut. Ack, I did it again. I keep writing Truffaut with an X, like, True-Faux, True-False, Truffaut the true-false father in whose premature death contained a fraction of Léaud’s. The trust and play already activated in this video—this shrugged, stuttered clip that contains, as I've been trying to tell you, everything: the teenager, the glimmering beginning and also the end, always already the end because Léaud begins and ends with Truffaut. "A perpetual immaturity," ascribed the 2024 Cyril Leuthy documentary about Léaud to Léaud, which is to say a perpetual attachment to the teenager and also to grief, to the death of the faux father, and an attachment to the grieving of the child who survived childhood against all odds, against embarrassment, and against the melancholy that was of course always behind Léaud’s forcefully proclaimed teenaged happiness. I’m in Marseille now. I got here a few days ago and have been so consumed writing this postcard inside an apartment that I haven’t seen the water yet, a fact I know would make you writhe with frustration—you’re on vacation! But it matters that I’m writing on this huge, green Formica desk—itself a vacation, dream, or state of grace—and I’ve been told that it was once used in a movie set. Like Léaud, I am most at ease at Place Monge in Paris, wearing a jacket in mild weather, holding a book that is dry, eyes protected from the sun. The final scene of this postcard will, however, take place at the water, in a final bow to The 400 Blows. Rimbaud died here in Marseille, did you know that? I’ll say more about him in my next note—his relation to Truffaut and Léaud—this rhyming triplet of their sensibilities!—translation and acting, the words “clownish” and “blank” next to the words “comic” and “wild.” OK, I’m off. I’m going to the sea with a plan to throw this postcard into it and hope that it finds you soon.