My Problematic Fave: A juicy question with many answers: Catherine Breillat. Dollarama. Nina Simone's version of "I Loves You, Porgy" (it's not on Simone, she saves it from Gershwin, it's just the one I love). I would say Woody Allen's Husbands and Wives or Deconstructing Harry, but I think it's okay to enjoy those (so bleak and revealing, they are basically a confession), it's more problematic that I love Manhattan.

First Movie I went on a Date for: Sweet Home Alabama, a double date with my neighbourhood friend and two guys from another school we met hanging out (as teens do) after school hours at the playground. He thought I was crying during an emotional scene where Reese Witherspoon visits a grave in her hometown (A grandparent? Childhood dog?), but I was a cynical 14-year-old, and not then or now a Rom Com girl, and was trying to muffle my laughter.

My Movie/TV Character Style Icon: Julia Stiles in Hamlet, Kiera Knightley in Love, Actually, Satine in Moulin Rouge, Maggie Cheung and Nathalie Richard in Irma Vep.

The First Sex Scene I Ever Saw: I can't remember for sure, but probably Titanic.

… and it made me feel: Confused: it gave me absolutely no information on what sex actually is, only that there were certain signals I would one day understand (like the men who laugh knowingly when they see the fogged up windows). Also afraid: it seemed sex would always leave some trace, and you could not hide it from anyone. Also romantic: sex was fun and actually fine, no one was hurt by it or punished for it (although it did happen right before they hit the iceberg, but this was not a coincidence that my young mind internalized.)

Best Needle Drop: Most of the songs in Rushmore (but maybe "Oo La La" by The Faces the most). I didn't even know what those songs were when I watched it at 15, but I knew that they were perfect.

I Wish this Fictional Meal Existed IRL: This meal does exist, but I have never seen the timpano from Big Night out in the wild, and although it seems like something that is better in theory than in execution, I'm not sure I'll feel fully satisfied if I never try one.

Untouchable Classic that I hate: How do I even pick! Citizen Kane does very little for me (except Welles, who I find quite hot), 2001: A Space Odyssey is glacial and so British (I do think the scene approaching the monolith on the moon is fab), Bresson leaves me dry (a symptom, perhaps, of him casting actors because they're hot), I find Parasite shallow, I only like the scenes in Stalker before and after they go to the Zone, and I can't get past Jeanne Dielman's melodramatic ending (which became an irritating staple of art house film).

Celebrity I had on my wall as a teen

Frank Black Francis and Karen O.

My film/TV OTP is: I can't think of a time when I felt the ending of a film or show should have been different, I like when characters come together, I like when they fall apart.

The Reality TV Show I Would Win: I think it's obvious that my true place is not as a competitor, but as a judge.

Many of my memories of the Columbine High School massacre concern the ensuing pop culture fallout. This was chiefly because I was a showbiz-pilled preteen boy at the time and the things that were misguidedly taking the lion’s share of the blame in the media for this horrific tragedy—The Matrix, Marilyn Manson, Doom—were also things that I was developing a rabid interest in. With my newly acquired subscription to Entertainment Weekly, I would read stories regarding Hollywood’s anxious course-correction for upcoming releases, like how that summer’s much-anticipated (for me) teen thriller, Teaching Mrs. Tingle, had to be delayed, recut and retitled from Killing Mrs. Tingle due to the sudden widespread furor over teen violence in the movies.

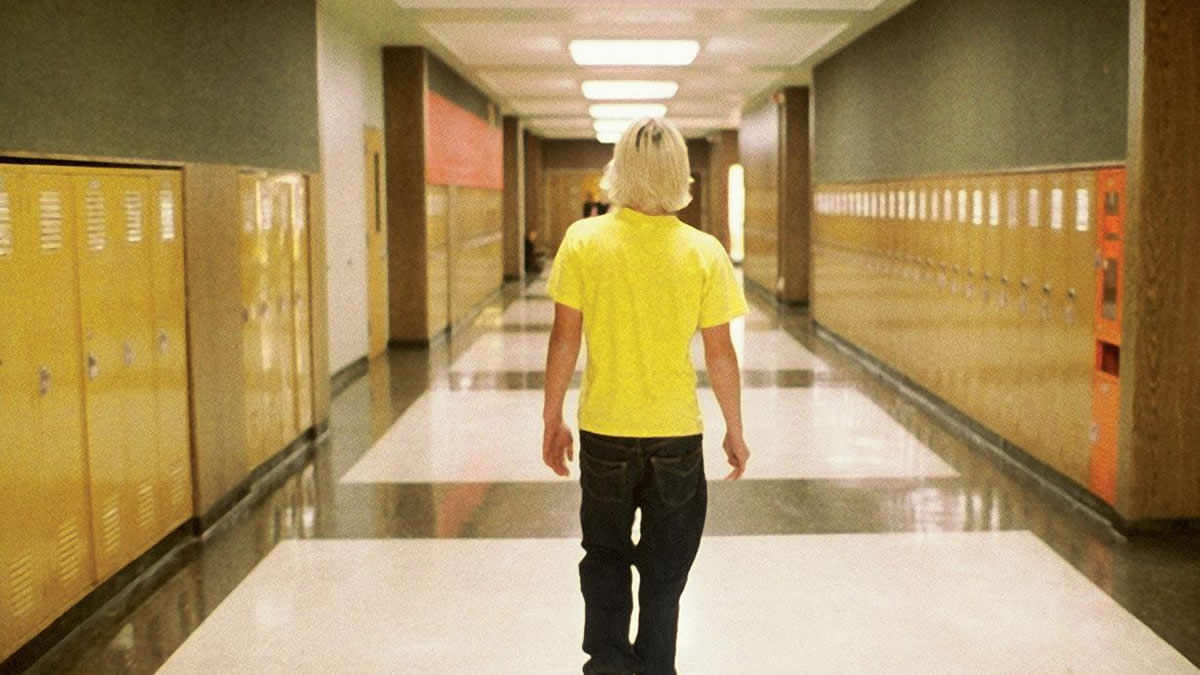

As with any highly-publicized true crime event, it wouldn’t take too long for the movies to gravitate back to the events of April 20, 1999. Michael Moore would emphatically kick open the door on the documentary front with the Oscar-winning Bowling for Columbine, a film that most people remember for featuring a surprisingly composed interview with the oft-blamed Manson and an unhinged one with Hollywood legend and lunatic NRA president Charlton Heston. Soon after, Gus Van Sant would then win the 2003 Palme d’Or for Elephant, his thinly-fictionalized recreation of a banal morning at a suburban high school that gives way to sudden detached violence. Seeing Van Sant’s hypnotically doom-laden film as a high-schooler really shook me up, crystallizing a nightmare scenario that I’d already begun vaguely playing out in my mind as school shootings became more commonplace in the years since Columbine. But this was only the most notable entry in a larger wave of narrative cinema during the mid-aughts that attempted the dubious task of Columbine depiction, which, for a budding film freak and voracious Crime Library reader like myself, became a way to process and understand an event that seemed so unfathomable.

Preceding Van Sant was none other than the infamous Uwe Boll, whose own Columbine-inspired exposé, Heart of America, came out in 2002. Boll also sets his film at an anonymous suburban high school during the morning leading up to a school shooting, as he flits between a dozen or so storylines and tons of different characters. But contrary to Elephant’s stark realism, Heart of America instead offers a litany of corny soap opera melodramas—including a teen pregnancy storyline featuring a pre-fame Elisabeth Moss—while we’re made to guess who amongst the school’s denizens will become the victims of the two bullied school shooters (styled, like in many of these films, to look exactly like the real Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold). Nevertheless, in an attempt to make a Statement™, Boll sombrely closes the film on reams of text stating all of the various school shootings that had happened up until the time of his film’s production. Who better to tackle the teen violence epidemic than the belligerent German man who would go on to literally beat his critics to a pulp in the boxing ring?

"Who better to tackle the teen violence epidemic than the belligerent German man who would go on to literally beat his critics to a pulp in the boxing ring?"

2002 also saw the release of Bang Bang You’re Dead, a television movie based on William Mastrosimone’s controversial school-shooting play that spookily premiered on stage at Thurston High School in Springfield, Oregon less than two weeks before Columbine happened. Inspired by a trio of earlier incidents, including a shooting at its debut venue, the play was written to be performed by and for high school students, in order to hopefully deter any possible perpetrators who might be in the audience. Mastrosimone subsequently updated his conceit for a post-Columbine era by adding a meta-twist on the film version, which follows a troubled student (a young Ben Foster), back at school after a suspension for calling in a bomb threat, who is given a chance to star in the titular play by the drama teacher who has faith in him (Ed’s Tom Kavanagh).

Some might find it a little inappropriate to cast a disturbed kid as a school shooter for some kind of high school drama therapy—but hey, it works here! The protagonist overcomes his antisocial tendencies and even thwarts a whole new massacre planned by a group of disgruntled students. While Mastrosimone’s heart is in the right place, the movie becomes an unintentionally funny Hamlet 2 scenario, with the drama class having to rebelliously take the play off-campus after it sparks the ire of parents and school administrators. (It’s okay, the play is ultimately allowed back on campus, and everyone is very moved by it.)

A similar mawkishness hampers Home Room, starring Erika Christensen and Busy Philipps as two teen survivors of a school shooting. Even though writer-director Paul F. Ryan talked to students, faculty, and parents of Columbine during pre-production, the movie still revolves around the clichéd narrative of two girls, one a popular honour roll student and one a troubled Goth kid from a broken home, discovering they just might have more in common than they realized in the wake of their shared grief. More effective is the found-footage entry Zero Day, released to theatres the very same week as Home Room in early September 2003 (just in time for the start of the school year). Inspired by the real journals and recordings that Harris and Klebold left behind, director Ben Coccio’s faux video diary of two teens planning an attack on their school takes a respectable stab at an authentic-feeling psychological portrait of a pair of young killers. At the same time, the Blair Witch-esque website that accompanied the film’s release and insinuated that its fictional killers and events were real was maybe a bit much.

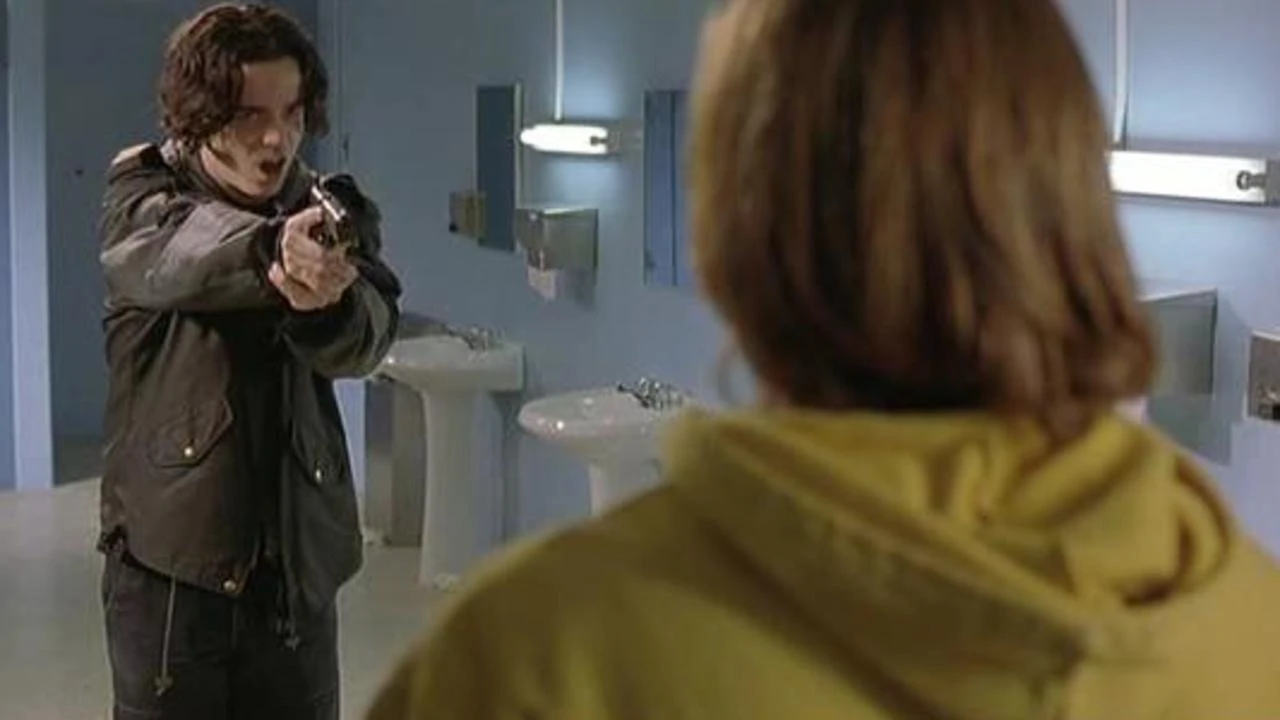

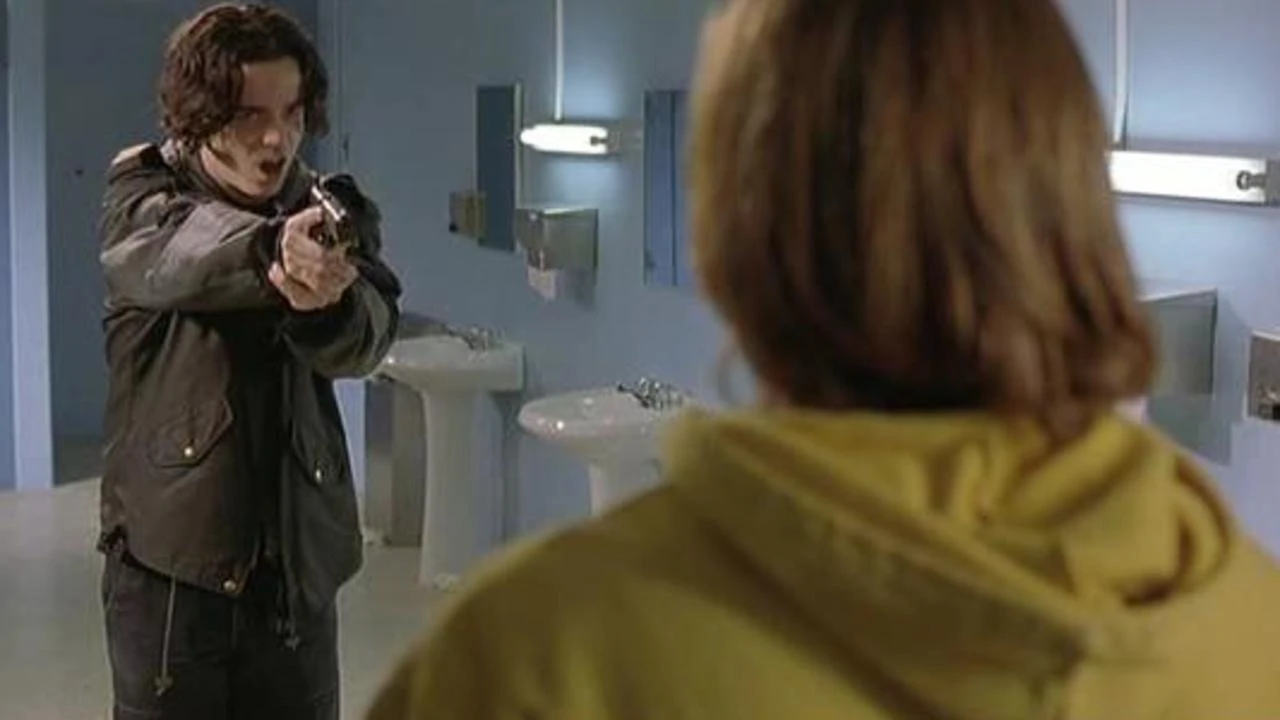

Canada would soon get its own notable bit of Columbine-sploitation with 2004’s two-part installment of Degrassi: The Next Generation entitled “Time Stands Still”. A pop culture touchstone for millennials in the Great White North and beyond, this very special episode concerned school loner Rick, who is routinely ostracized and bullied by the popular kids (he was abusive towards his girlfriend and put her in a coma the season prior, so it wasn’t totally unjustified). When he gets a bucket of paint and feathers dumped on him, he snaps and brings a gun to school. This episode is mainly notable for the introduction of “Wheelchair Jimmy”, as Aubrey “Drake” Graham’s character is shot in the back and paralyzed from the waist down for the remainder of his time on the series. Watching it at the time, the whole ordeal felt oddly intimate and it affected me deeply. Not only was Jimmy a good basketball player who could have had a chance at the big leagues, but after three seasons watching these Toronto-area students, they all felt like my friends.

More recently, Columbine-sploitation re-emerged as a right-wing reactionary fantasy. In 2016, Pure Flix, the major Christian studio behind the God’s Not Dead series, released I’m Not Ashamed, based on the journals of Columbine victim Rachel Scott. Scott was the first student killed in the Columbine massacre and was instantly turned into a Christian martyr for ostensibly being murdered for her faith, something that has been heavily disputed. Nevertheless, Scott’s parents subsequently made a lot of money hawking the value of their daughter’s faith-based life, resulting in a movie that imagines made-up scenarios to fit the usual Pure Flix obsession with Christian persecution in America.

A few years later, conservative producer Dallas Sonnier would sneak Run Hide Fight into the Venice Film Festival, a film that reframes the school shooting scenario as an unadulterated action romp. Subsequently dumped to streaming on The Daily Wire, the film expectedly insinuates the pernicious idea that maybe everyone should actually have a gun for, you know, protection and stuff. At the same time, I can’t deny there’s something about the idea of teenagers taking control of their turf and violently retaliating against school shooters that satisfies the basic tenets of exploitation cinema. Hey, if Quentin Tarantino’s name were on this film instead of the guy who won the second season of Project Greenlight, it would probably already be recognized as a modern classic.

The most potent example of Columbine-sploitation, however, is the first one ever made. In October 1999, shot-on-video horror impresarios William Hellfire and Joey Smack unleashed Duck! The Carbine High Massacre, a response to the distasteful and erroneous media coverage of Columbine. With the directors starring as two trench-coat wearing high school killers, the film is a grungy and morbidly funny DIY affair that isn’t afraid to provoke, announcing its intentions right off the top with a prescient title card that states:

“We realize that some people may consider this movie offensive, obscene, sacrilegious and thoroughly disgusting. However it was bound to become a motion picture eventually, or even worse, a ‘made-for-TV’ movie. So we decided to do it first. God Bless America!”

Duck! doesn’t hide its base intentions as a crude prank, one that even got its filmmakers arrested at one point for the possession of weapons on a school property. But it also places the events of Columbine within a wider context of unbridled American rot, daring to show the amorality of school shooters as being inspired as much by the behaviour of the adults around them as by anything else. More importantly, the film was made by a group of early-twentysomething filmmakers close enough in age to tangibly feel Columbine’s immediate reverberations and who felt a kinship with the Goth kids and other outsiders who were consistently demonized by the media and religious groups in the wake of the shooting.

Ironically, Duck! struggled to find further distribution past its initial premiere until more “respectable” Columbine-inspired movies made by older adults started cropping up. And while most of these movies work themselves into knots trying to come up with palatable explanations as to why something this horrible happened (and, of course, regularly continues to happen), Duck! is right there in the hallways with the kids, festering like a wound that has never healed.

Many of my memories of the Columbine High School massacre concern the ensuing pop culture fallout. This was chiefly because I was a showbiz-pilled preteen boy at the time and the things that were misguidedly taking the lion’s share of the blame in the media for this horrific tragedy—The Matrix, Marilyn Manson, Doom—were also things that I was developing a rabid interest in. With my newly acquired subscription to Entertainment Weekly, I would read stories regarding Hollywood’s anxious course-correction for upcoming releases, like how that summer’s much-anticipated (for me) teen thriller, Teaching Mrs. Tingle, had to be delayed, recut and retitled from Killing Mrs. Tingle due to the sudden widespread furor over teen violence in the movies.

As with any highly-publicized true crime event, it wouldn’t take too long for the movies to gravitate back to the events of April 20, 1999. Michael Moore would emphatically kick open the door on the documentary front with the Oscar-winning Bowling for Columbine, a film that most people remember for featuring a surprisingly composed interview with the oft-blamed Manson and an unhinged one with Hollywood legend and lunatic NRA president Charlton Heston. Soon after, Gus Van Sant would then win the 2003 Palme d’Or for Elephant, his thinly-fictionalized recreation of a banal morning at a suburban high school that gives way to sudden detached violence. Seeing Van Sant’s hypnotically doom-laden film as a high-schooler really shook me up, crystallizing a nightmare scenario that I’d already begun vaguely playing out in my mind as school shootings became more commonplace in the years since Columbine. But this was only the most notable entry in a larger wave of narrative cinema during the mid-aughts that attempted the dubious task of Columbine depiction, which, for a budding film freak and voracious Crime Library reader like myself, became a way to process and understand an event that seemed so unfathomable.

Preceding Van Sant was none other than the infamous Uwe Boll, whose own Columbine-inspired exposé, Heart of America, came out in 2002. Boll also sets his film at an anonymous suburban high school during the morning leading up to a school shooting, as he flits between a dozen or so storylines and tons of different characters. But contrary to Elephant’s stark realism, Heart of America instead offers a litany of corny soap opera melodramas—including a teen pregnancy storyline featuring a pre-fame Elisabeth Moss—while we’re made to guess who amongst the school’s denizens will become the victims of the two bullied school shooters (styled, like in many of these films, to look exactly like the real Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold). Nevertheless, in an attempt to make a Statement™, Boll sombrely closes the film on reams of text stating all of the various school shootings that had happened up until the time of his film’s production. Who better to tackle the teen violence epidemic than the belligerent German man who would go on to literally beat his critics to a pulp in the boxing ring?

"Who better to tackle the teen violence epidemic than the belligerent German man who would go on to literally beat his critics to a pulp in the boxing ring?"

2002 also saw the release of Bang Bang You’re Dead, a television movie based on William Mastrosimone’s controversial school-shooting play that spookily premiered on stage at Thurston High School in Springfield, Oregon less than two weeks before Columbine happened. Inspired by a trio of earlier incidents, including a shooting at its debut venue, the play was written to be performed by and for high school students, in order to hopefully deter any possible perpetrators who might be in the audience. Mastrosimone subsequently updated his conceit for a post-Columbine era by adding a meta-twist on the film version, which follows a troubled student (a young Ben Foster), back at school after a suspension for calling in a bomb threat, who is given a chance to star in the titular play by the drama teacher who has faith in him (Ed’s Tom Kavanagh).

Some might find it a little inappropriate to cast a disturbed kid as a school shooter for some kind of high school drama therapy—but hey, it works here! The protagonist overcomes his antisocial tendencies and even thwarts a whole new massacre planned by a group of disgruntled students. While Mastrosimone’s heart is in the right place, the movie becomes an unintentionally funny Hamlet 2 scenario, with the drama class having to rebelliously take the play off-campus after it sparks the ire of parents and school administrators. (It’s okay, the play is ultimately allowed back on campus, and everyone is very moved by it.)

A similar mawkishness hampers Home Room, starring Erika Christensen and Busy Philipps as two teen survivors of a school shooting. Even though writer-director Paul F. Ryan talked to students, faculty, and parents of Columbine during pre-production, the movie still revolves around the clichéd narrative of two girls, one a popular honour roll student and one a troubled Goth kid from a broken home, discovering they just might have more in common than they realized in the wake of their shared grief. More effective is the found-footage entry Zero Day, released to theatres the very same week as Home Room in early September 2003 (just in time for the start of the school year). Inspired by the real journals and recordings that Harris and Klebold left behind, director Ben Coccio’s faux video diary of two teens planning an attack on their school takes a respectable stab at an authentic-feeling psychological portrait of a pair of young killers. At the same time, the Blair Witch-esque website that accompanied the film’s release and insinuated that its fictional killers and events were real was maybe a bit much.

Canada would soon get its own notable bit of Columbine-sploitation with 2004’s two-part installment of Degrassi: The Next Generation entitled “Time Stands Still”. A pop culture touchstone for millennials in the Great White North and beyond, this very special episode concerned school loner Rick, who is routinely ostracized and bullied by the popular kids (he was abusive towards his girlfriend and put her in a coma the season prior, so it wasn’t totally unjustified). When he gets a bucket of paint and feathers dumped on him, he snaps and brings a gun to school. This episode is mainly notable for the introduction of “Wheelchair Jimmy”, as Aubrey “Drake” Graham’s character is shot in the back and paralyzed from the waist down for the remainder of his time on the series. Watching it at the time, the whole ordeal felt oddly intimate and it affected me deeply. Not only was Jimmy a good basketball player who could have had a chance at the big leagues, but after three seasons watching these Toronto-area students, they all felt like my friends.

More recently, Columbine-sploitation re-emerged as a right-wing reactionary fantasy. In 2016, Pure Flix, the major Christian studio behind the God’s Not Dead series, released I’m Not Ashamed, based on the journals of Columbine victim Rachel Scott. Scott was the first student killed in the Columbine massacre and was instantly turned into a Christian martyr for ostensibly being murdered for her faith, something that has been heavily disputed. Nevertheless, Scott’s parents subsequently made a lot of money hawking the value of their daughter’s faith-based life, resulting in a movie that imagines made-up scenarios to fit the usual Pure Flix obsession with Christian persecution in America.

A few years later, conservative producer Dallas Sonnier would sneak Run Hide Fight into the Venice Film Festival, a film that reframes the school shooting scenario as an unadulterated action romp. Subsequently dumped to streaming on The Daily Wire, the film expectedly insinuates the pernicious idea that maybe everyone should actually have a gun for, you know, protection and stuff. At the same time, I can’t deny there’s something about the idea of teenagers taking control of their turf and violently retaliating against school shooters that satisfies the basic tenets of exploitation cinema. Hey, if Quentin Tarantino’s name were on this film instead of the guy who won the second season of Project Greenlight, it would probably already be recognized as a modern classic.

The most potent example of Columbine-sploitation, however, is the first one ever made. In October 1999, shot-on-video horror impresarios William Hellfire and Joey Smack unleashed Duck! The Carbine High Massacre, a response to the distasteful and erroneous media coverage of Columbine. With the directors starring as two trench-coat wearing high school killers, the film is a grungy and morbidly funny DIY affair that isn’t afraid to provoke, announcing its intentions right off the top with a prescient title card that states:

“We realize that some people may consider this movie offensive, obscene, sacrilegious and thoroughly disgusting. However it was bound to become a motion picture eventually, or even worse, a ‘made-for-TV’ movie. So we decided to do it first. God Bless America!”

Duck! doesn’t hide its base intentions as a crude prank, one that even got its filmmakers arrested at one point for the possession of weapons on a school property. But it also places the events of Columbine within a wider context of unbridled American rot, daring to show the amorality of school shooters as being inspired as much by the behaviour of the adults around them as by anything else. More importantly, the film was made by a group of early-twentysomething filmmakers close enough in age to tangibly feel Columbine’s immediate reverberations and who felt a kinship with the Goth kids and other outsiders who were consistently demonized by the media and religious groups in the wake of the shooting.

Ironically, Duck! struggled to find further distribution past its initial premiere until more “respectable” Columbine-inspired movies made by older adults started cropping up. And while most of these movies work themselves into knots trying to come up with palatable explanations as to why something this horrible happened (and, of course, regularly continues to happen), Duck! is right there in the hallways with the kids, festering like a wound that has never healed.